A Dam for the People

Wilson Dam was built for WWI, but the war ended before it could spin up its turbines. After years spent in limbo, the dam gained new purpose with the founding of TVA...

For more than a century, Alabama’s Muscle Shoals—a series of irregular rock formations that formed shallow and often turbulent pockets of rushing current—had stood in the way of navigation and commerce on the Tennessee River. The shoals slowed the movement of goods to and from upstream farms and the travel of settlers to new farming lands to the west. The coming of the steamboat and the growth of large cotton plantations along the river bottomlands in the early 1800s stimulated the state and federal governments to seek ways of taming the treacherous shoals. But these efforts—involving both a canal around the shoals and a system of locks and gates—were largely unsuccessful.

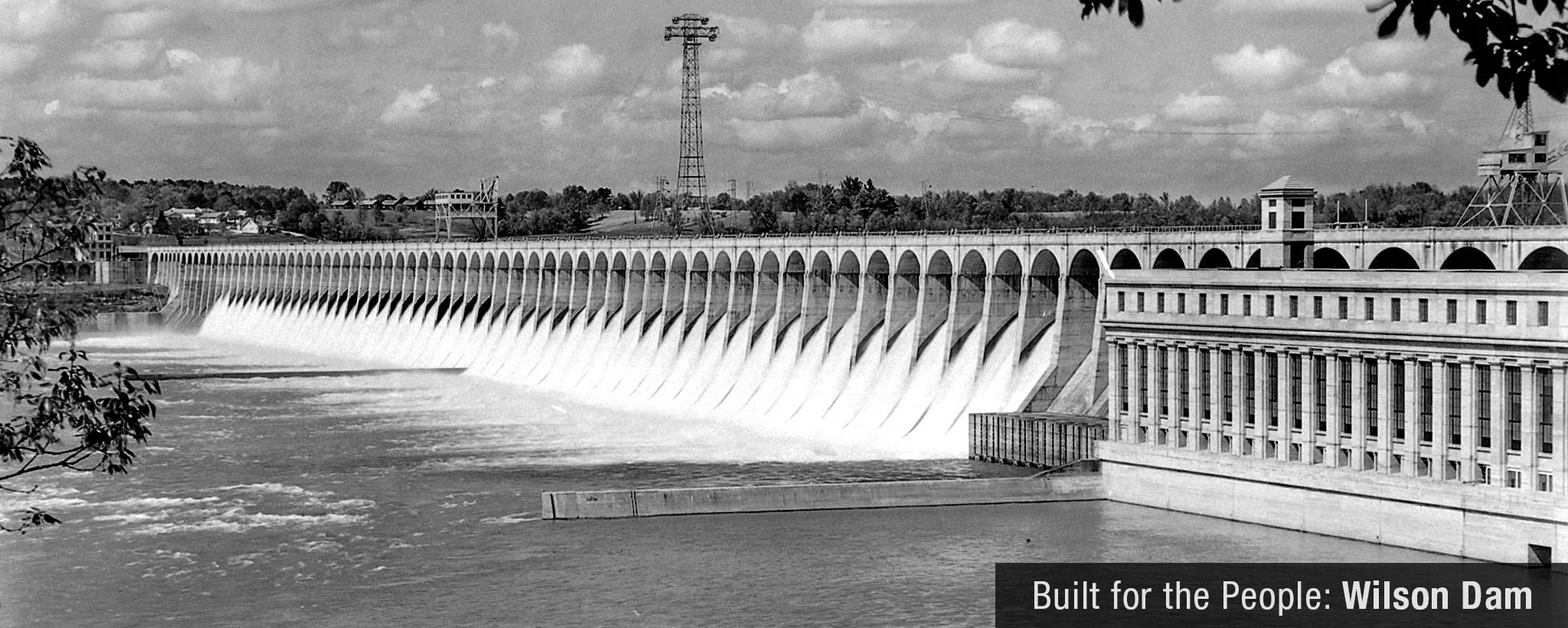

It was not until Wilson Dam was completed in 1925 that the treacherous Muscle Shoals were finally buried under a new reservoir allowing steamboats and barges to travel this stretch of the river unhampered.

Ironically, however, Wilson Dam was not constructed primarily to erase the shoals as a navigation hazard. The water pouring over the massive rock formations at the Shoals represented hydroelectric energy sorely needed in World War I weapons manufacturing.

Nitrates Needed

America’s decision to enter World War I made Congress fear that the nation’s supply of nitrates, an essential ingredient in the production of explosives, would be terminated by German naval operations. The United States still relied on guano—bat dung—imported from Chile as the source of this critical military resource; deliveries could easily be interrupted by U-boats.

To solve this potentially disastrous problem, the National Defense Act of 1916 authorized immediate construction of two nitrate plants to be powered by an adjacent hydroelectric facility. Government engineers selected Muscle Shoals, located on the Tennessee River, as the construction site. Surveys noted that it had the most potential for the development of water power east of the Rockies. Construction on the dam began in 1918.

The war ended, however, before the facilities could ever begin production. And the U.S. government was saddled with a stranded asset worth $130 million dollars.

Henry Ford offered to buy the nitrate plants and the power from Wilson Dam for $5 million, envisioning the creation of a giant industrial city at Muscle Shoals that ultimately would employ a million workers. But Senator George Norris of Nebraska found that price laughable, and for years led the fight for public ownership.

The issue was finally settled in May of 1933 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a bill creating the Tennessee Valley Authority, an independent agency of the federal government charged with broad responsibility for the unified development of all the resources of the Tennessee Valley.

Putting the Dam to Work

TVA converted the long-idle nitrate plant to fertilizer research and production. Wilson Dam became the cornerstone in TVA’s unified plan for development of the entire Tennessee River. Thirteen generators were added to the original eight, making Wilson the largest hydroelectric installation in the TVA power system.

While a substantial portion of the original Wilson Dam structure remains intact, alterations have been made to improve the efficiency of the facility. Perhaps the most significant of these was the construction of a new lock which, when completed in 1959, was the largest single-chamber lock in the world. The chamber, located on the river side of the original lock, measures 110 by 600 feet and has a lift-type upper and miter-type lower gate.

From 1959 to 1961, three additional generating units were installed on an outdoor station constructed on the west face of the dam at the northern end of the existing generating facilities, increasing the production capacity of the dam to 598,000 kilowatts. From 1965 to 1968, the nine original generating units were modernized and encased in air housings to allow more efficient cooling and to contain carbon dioxide in the event of fire within the units. With that project, the production capacity of Wilson Dam rose to 629,840 kilowatts—the highest level of production of any hydroelectric facility in the TVA system.

Though it was built by the Army Corps of Engineers, Wilson Dam stands as a testament to the effectiveness of TVA, an independent, government-owned corporation. It marked the first attempt in the United States to conserve and develop natural resources on a regional scale. And as it has since it passed into TVA hands, it provides multiple benefits to the people of the Tennessee Valley. Today, Wilson is one of 32 major dams that work together to provide flood control, navigation, electrical power and the benefits of recreation and water supply to the people of the Tennessee Valley.