Norris Dam: “No Flood of Worry”

During WWII, Ernie Pyle described the fighting in simple language. But his fame began before the war, when he set out to explain the American experiment called TVA, being built at Norris Dam.

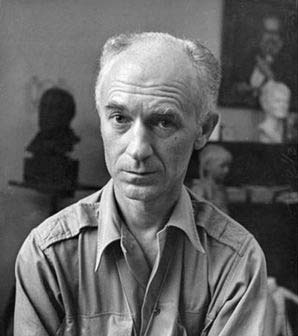

Everyone old enough to remember World War II knows the name Ernie Pyle. And 55 years after his death millions still think of him as a friend, even if they knew him only from his newspaper photos, a smiling,

humble-looking middle-aged guy in an unbuckled helmet.

Everyone old enough to remember World War II knows the name Ernie Pyle. And 55 years after his death millions still think of him as a friend, even if they knew him only from his newspaper photos, a smiling,

humble-looking middle-aged guy in an unbuckled helmet.

When you asked someone in 1945 if they’d read Ernie’s column, they didn’t say, “Ernie who?” Probably the best-known war correspondent of the entire 20th century, Pyle wrote dispatches about the common man’s war in Europe and the Pacific that brought the conflict vividly home to families across America.

He was there in the earliest days, when it looked as though the other guys might win the war, and he had no career after the war; in the final weeks of the fighting, a Japanese sniper’s bullet ended his career, and his life.

Chronicler of American Life

But Ernie Pyle was well known even before World War II, as a newspaper columnist for Scripps-Howard. Beginning in the mid-’30s, he roved around the country writing about interesting people and places. He filed an astonishing six columns every week—pieces that made him, by some estimates, the most popular writer in America. One of his favorite subjects was President Roosevelt’s new experiment, TVA.

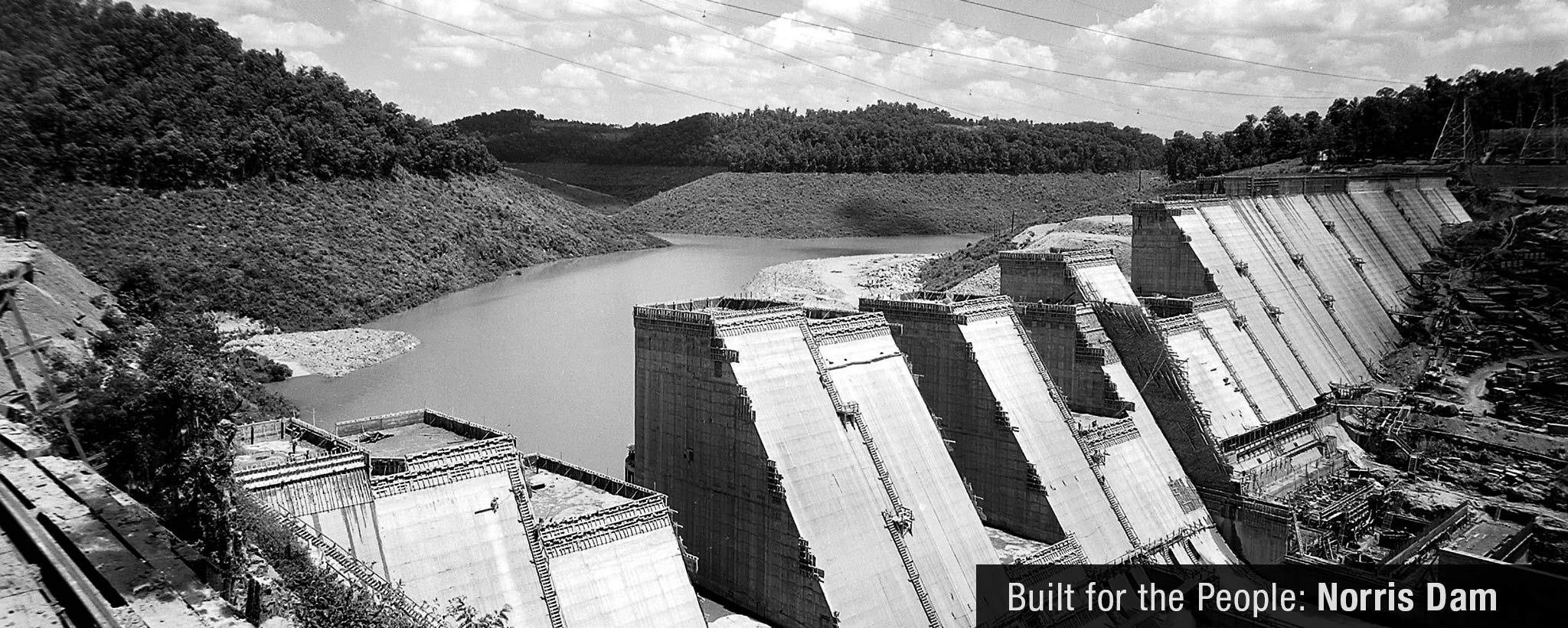

In 1935, only weeks after Pyle began his column, he drove his Ford into the Tennessee Valley region and went out on a chilly fall day to get a look at the famous Norris Dam, still under construction.

A small, skinny man of 35, he was impressed that his TVA host could walk right out onto the dam—it had no guardrail yet—and “look straight down 15 stories” to the pool in the Clinch River below. “When I look over the edge of Norris Dam,” he confessed, “I get down on my knees and elbows, take a death grip on a couple of steel rods sticking out of the cement, and then just peer over, a little at a time.”

But, Pyle wrote, he had a mission. “TVA is one of those things that everybody knows exist but few people (outside this valley) seem to make head or tail of. So I came down to give it the works. It is my ambition to be the first American to explore TVA so that a little child can understand it.”

Explaining TVA

In 1935 he devoted seven columns in a row to explaining TVA to the American people. “TVA, as nearly as I can figure out, is an attempt to do the same thing to a whole section of the United States that a doctor does to a man who is all smashed up in an auto accident. And that is, fix him up.”

Pyle tried to define daunting concepts like regional planning. “That term alone is enough to scare anybody off. A fellow I know in TVA thinks a better term would be ‘organized foresight.’ I think a still better one would be, ‘We fix up the Tennessee Valley.’”

“The big dams,” he stated, “are merely the foundation upon which TVA plans to build its castle.” He wrote about the dams, but he also covered every other major aspect of TVA, from navigation to agriculture to fertilizer production to erosion control. (“Don’t think erosion is some platitudinous New Deal word, either. It really is something actual, one of those insidious things like T.B. that we don’t take seriously until someone we know gets it.”)

During his first visit, he happened to catch sight of the TVA Nursery about the same time a tourist from Chicago did. She said, “That’s another one of those communistic things—the government raising babies!” In telling that story, Pyle added, “What they do, of course, is raise baby trees, millions of them, to be planted all over the valley.”

Coming Back to Norris

Pyle gave careful accounts of all TVA’s functions, but he was repeatedly drawn back to Norris Dam, which he described as no one else would have. “There is a terrific fascination about a growing dam,” he wrote. “The height, the hundreds of men scampering all over it . . . there is a boom, boom, boom about it that gives me the same rush that 42nd and Broadway gives some people.”

Ernie Pyle came to the upper Tennessee Valley region on at least four extended visits during his first five years as a national columnist. In early 1937 he wrote, “Norris Dam has grown up since I saw it last. The dam is bare, and immobile, and lonely, just standing there. Norris Dam is what it should be: finished, unromantic and working. The lake is blue, and the water is clear, and there is hardly a ripple on the shore. There is no flood worry on the upper Clinch River.

“That is the sense of Norris Dam. That’s what they put it there for in the first place. But I liked it much better during the putting.”

In one column Pyle assessed TVA as “a good dream,” then added, “and when you drive around here, it looks like a dream that has solid stuff in it.” He suggested that his native Midwest could use something along the lines of TVA.

During his stays in the TVA region, he wrote about other things, too: a farmer’s auction in Greeneville, Tenn.; a book factory in Kingsport; the elderly man who’d been Andrew Johnson’s slave, still working as a baker in a Knoxville cafe. Pyle’s last visit to the region may have been in October 1940, more than 75 years ago, when he wrote a series of pieces about moonshining in Cocke County.

The war, the most famous part of his career, and the end of it, were just ahead.