Germ Fighter

Early in her life, Miss Elma Rood fought the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918. Then she brought what she learned to the Tennessee Valley to instill good hygiene practices that resonate today.

COVID-19 is a novel virus, and it’s taking a toll on the country now. But it’s not the first pandemic to rattle these shores. TVA is working hard to do what it can to contain and to help cope with the situation. And from its beginnings, personnel — one in particular — understood lessons learned from the last go-round with a worldwide contagion.

Miss Elma Rood was about 56 years old when she came to work for TVA. Born in Faribault, Minnesota, in 1879 to immigrant parents, she studied nursing at Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. Graduating in 1914, she worked in private nursing for a few years before she was recommended by her supervisor to join the American Red Cross. In his recommendation of Elma, her supervisor reported that she had a pleasing personality, she was neat and refined and she had above-average initiative and good executive ability. “Her standing as a nurse and as a woman since graduation was excellent.”

Parallels to COVID-19

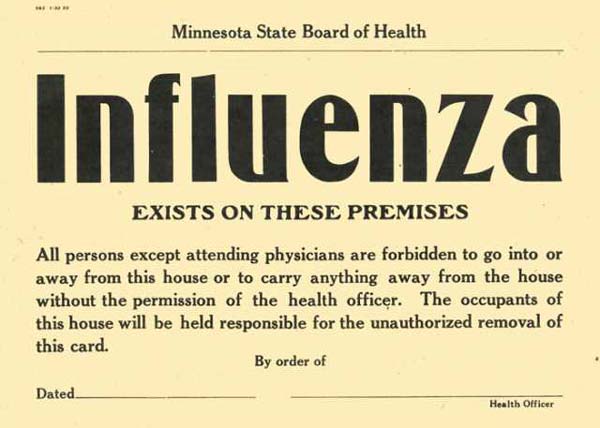

Assigned to duty in the North Division Office in June 1918, she organized classes in home hygiene and care of the sick as part of the new Red Cross peacetime program. She was soon sent to Fort Snelling, Minn. The hospital there admitted its first case of influenza on September 27. Within ten days, 850 patients had been admitted, most with what would become known as “the Spanish flu.” Two hundred of those developed pneumonia, with 61 deaths. Most of the patients were men under the age of twenty who had enrolled in the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) at the University of Minnesota. Close contact in classrooms and barracks was likely the cause of the explosive spread of the infection. The epidemic peaked there around October 15.

To reduce the spread of the flu, health officials directed Minnesotans to rest, use handkerchiefs, go to bed and contact a doctor if symptoms arose. The actions taken in 1918 mirror our world today: they discouraged standing in crowds, spitting on floors and sidewalks, and sharing drinking cups and towels. Government officials throughout the state closed public spaces in an attempt to prevent the spread of the flu. Schools, libraries, dance and pool halls, theaters, bowling alleys, churches and lodge halls were shuttered. Public events such as parties, meetings, and funerals were banned. Operating elevators in buildings with less than seven stories was prohibited to reduce human contact. Streetcar drivers were directed to keep their windows open so that fresh air could circulate; the number of riders allowed was reduced. Retail businesses could not advertise sales and their hours were regulated.

After what must have been a harrowing few months caring for victims of the Spanish flu, the Red Cross discharged Elma from service at the end of December 1918.

Moving from Minnesota

In the early 1920s, she taught nursing and health at Columbia University in New York before moving on to Mansfield, Ohio, where she served for several years as Director of Health Education for the Child Health Demonstration organization. Newspapers around the country reported on her successful work for this organization. The Mexia Daily News in Mexia, Texas, reported that normal school students —women training to be teachers — from around the country would travel to Mansfield for a two-week course in health education led by Rood. In fact, when she determined it was time to leave, a banquet was held in her honor. This toast was published in the 1926 Manchester Yearbook demonstrating her high regard in the community:

“We look better, feel better, are better we hope/All due to Miss Rood and to not taking dope,

She gives us such pep our work to do/I know this is true and I think you do too.

No matter how lukewarm we were at the start/We now do our health work right from the heart,

The children all love her, the parents as well/And we all will miss her for quite a long spell.”

Coming to TVA

Moving from Ohio to Nashville, Tenn., in the late 1920s, Rood taught at the George Peabody College for Teachers. She then joined TVA in its earliest days in the 30s, making her home in Knoxville at Fort Sanders Manor. While at TVA, she developed her program about the importance of the school nurse in school health and health education. It is likely she traveled around the Tennessee Valley, meeting with principals of the schools in the region and in TVA’s construction camps, presenting her program and educating all on public health issues.

By June 30, 1936, Miss Rood had returned to the Nashville area, and by 1940, at the age of 61, she was living and teaching at Madison College in Davidson County, Tenn. The school had its own printing business, The Rural School Press, which published a number of Elma’s books on health education, such as Tuberculosis Education: A Guide for Professional and Lay Workers, 1936. In a popular newspaper column called “Answers to Questions by Frederic J. Haskin,” the question was asked in Sept. 1937, Is tuberculosis inherited? The answer was given as “According to Elma Rood in Tuberculosis Education she states definitely that it is not inherited. It is caused by a germ.”

It seems that Elma, a recognized expert, spent her entire life educating about good health practices. In her later years, Elma returned to Minnesota where she died at the age of 92.