The Artist With a Camera

When TVA set out to transform life in the Valley, Charles Krutch set out to capture the process on film. The result was high art.

A middle-aged man with a white-collar job at TVA might find it hard to imagine the products of his work displayed as art—much less hanging in the renowned Museum of Modern Art in New York, N.Y.

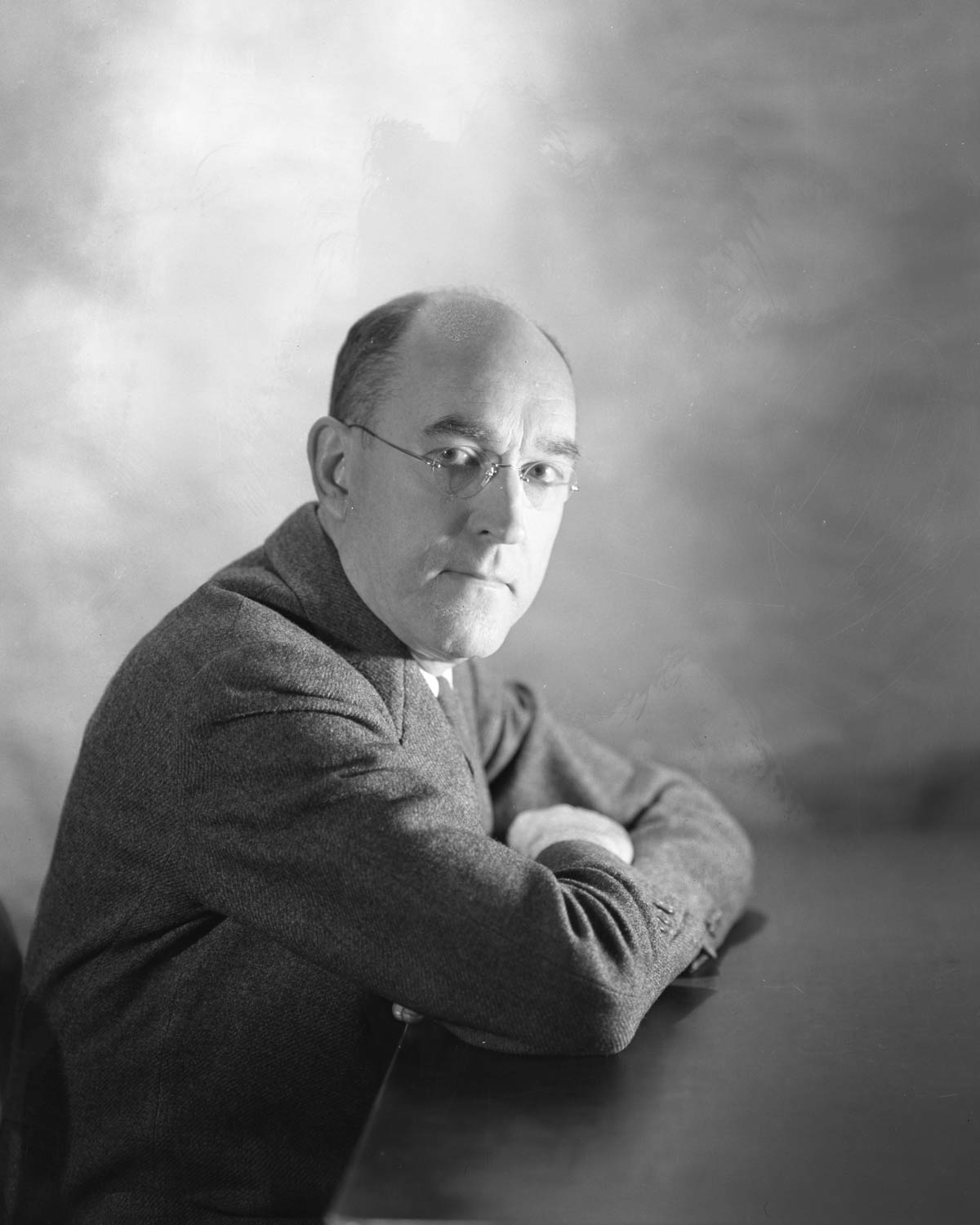

But photographer Charles Krutch (pronounced "Krootch") was probably a bit different from most of the people sitting at TVA desks in the agency’s early years. The grandson of German immigrants with aristocratic airs, Krutch documented the transformation of the Tennessee Valley by TVA in the 1930s and ’40s, and in the process created photographs acclaimed for their artistry.

Eccentric Artistry

The Krutches were perhaps the single most talented and eccentric family in Victorian Knoxville, Tenn. One uncle was a charmingly erratic church organist and impressionist painter, another a concert pianist. Charles’s younger brother, Joseph Wood Krutch, moved to New York and became a famous author and theater critic for The Nation magazine.

Ill as a child and not expected to survive to adulthood, Charles rarely attended school and never finished high school. He remained single through his twenties and thirties, dabbled in photography and did some work for a local newspaper. He didn’t really need a job, having inherited a good deal of money as a result of his father’s successful business dealings.

Charles Krutch was 47 when he took a job with TVA’s Information Division in 1934, the second year of the agency’s existence. It wasn’t a terribly glamorous occupation, at least not at first. Krutch was a record keeper and a staff photographer. His job was to document TVA’s mammoth construction projects as they went up.

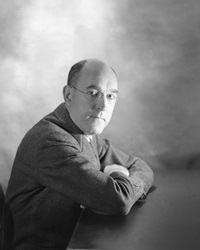

Charles Krutch, photographed in 1941.

Co-workers observed that it might have been his possession of independent means that emboldened him to do things his own way. If he was going to take photographs, he said, he’d take very good ones. He experimented with red filters, and shot many photographs at night to sharpen the contrasts. Some people grumbled about the liberties he took, but no one fired him.

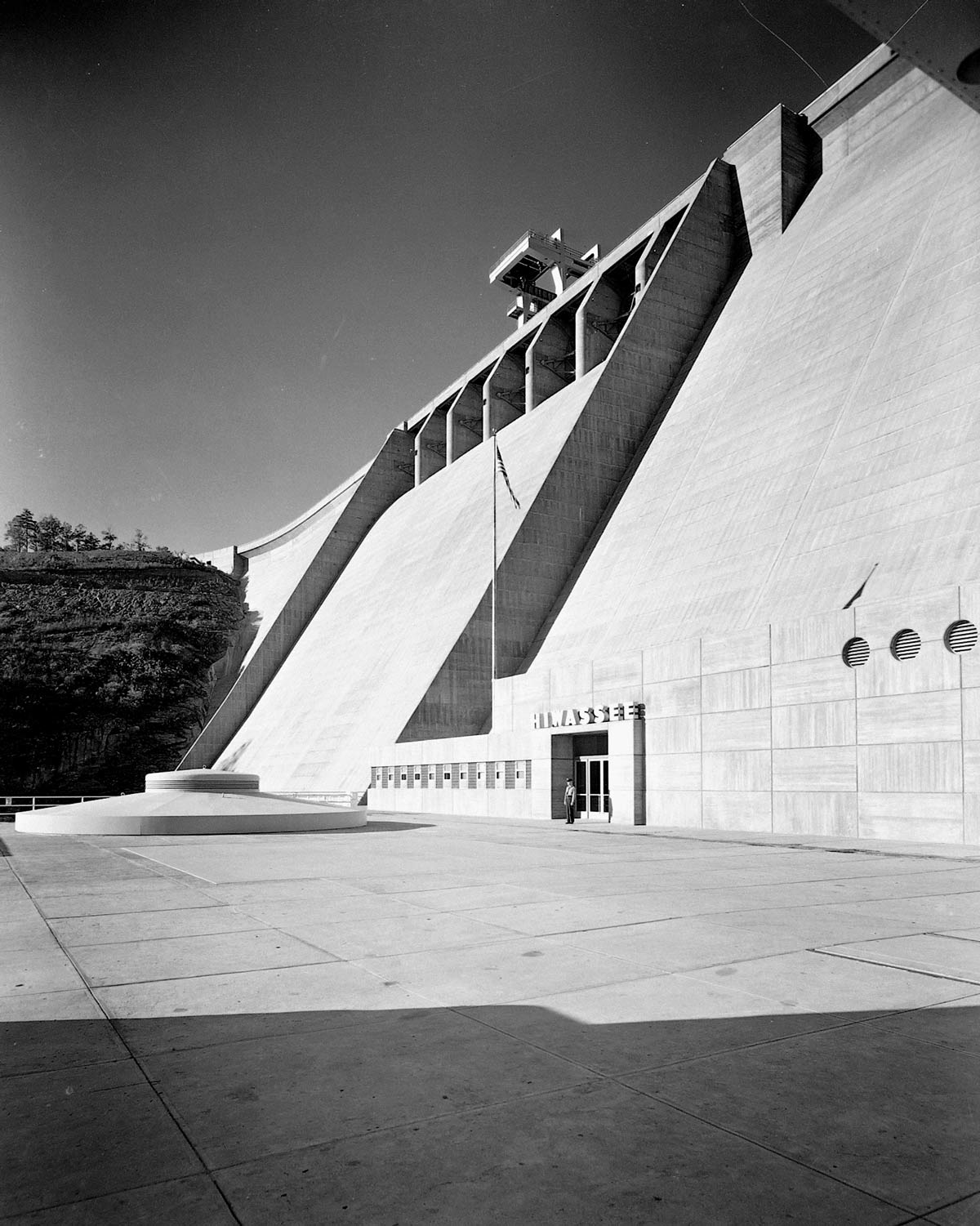

Photographing dams and generators, sheet mills and munitions plants, Krutch played with shapes and shades as few other photographers at federal agencies had ever dared to do. Some of his pictures looked like modernist paintings, dynamic studies in black and white. In a day when photography was barely considered a fine art, Krutch earned a reputation as an artist with a camera.

Ageless Beauty

His photography attracted notice. He’d been at it only three years when, in a 1937 retrospective on the first century of photography, The New York Times featured a Krutch photo of Norris Dam as emblematic of what could be done with a camera.

A photographic exhibition opened at the Museum of Modern Art in May 1941. It showcased 250 photographs of TVA projects, all of them taken by Krutch and his colleague Emil Sienknecht. Among the photographs that big-city museumgoers gawked at were striking Krutch shots of giant generators at Pickwick, a huge crane at Wheeler Dam and Chickamauga Dam’s spillway at night.

A writer for the photography magazine U.S. Camera was there, and was impressed. “Red filters were used to make the subjects stand out boldly against a dark sky; deep shadows accentuate the hugeness of masses; wide-angle lenses and exaggerated perspective produce extraordinary effects. An illusion of depth, texture and form is everywhere.”

The New York Times raved, “The beauty of these dams . . . is ageless; it is the honest beauty of a fine tool, shaped by the purpose of its use. This is architecture of lasting worth. Why shouldn’t we insist that other government architecture be equally designed?” You can’t help wondering how much Krutch’s photography contributed to the strength of the impression.

By 1944, when a landmark book called “The Valley and Its People” was nationally published by Knopf, Charles Krutch was the respected chief of TVA’s graphics department. Not surprisingly, the book was illustrated largely with Krutch’s dramatic photographs; today it’s the handiest place to go for a good look at his work.

A Living Heritage

Krutch went on quietly performing his duties at TVA into the 1950s, well past the usual retirement age. Instead of eating lunch with colleagues, the tall, razor-thin photographer would spend his lunch break at the stock brokerage, buying and selling. He and his wife lived in a nice subdivision house on the west side of town, but few of their acquaintances guessed that this mild-mannered TVA employee was a millionaire. He died in October 1981, at the age of 94.

Jaws dropped weeks later when his lawyer read Krutch’s will: he’d left more than a million dollars to the city of Knoxville for the establishment of a downtown park. “A quiet retreat with trees, shrubs, and flowers,” it stipulated, “for the pleasure and health of the public.” The lack of a downtown park was something Knoxvillians had been grumbling about since Krutch’s sickly boyhood.

Today Krutch Park sits one block south of TVA headquarters. Taking up almost half a city block, it contains a small waterfall, a stream flowing into a pond, and lots of trees, shrubs and flowers. During the spring and summer, it’s green and lush. Krutch’s legacy of beauty lives on in his remarkable photographs, and in the park that bears his name.