Articles

Secrets Inside the Mountain

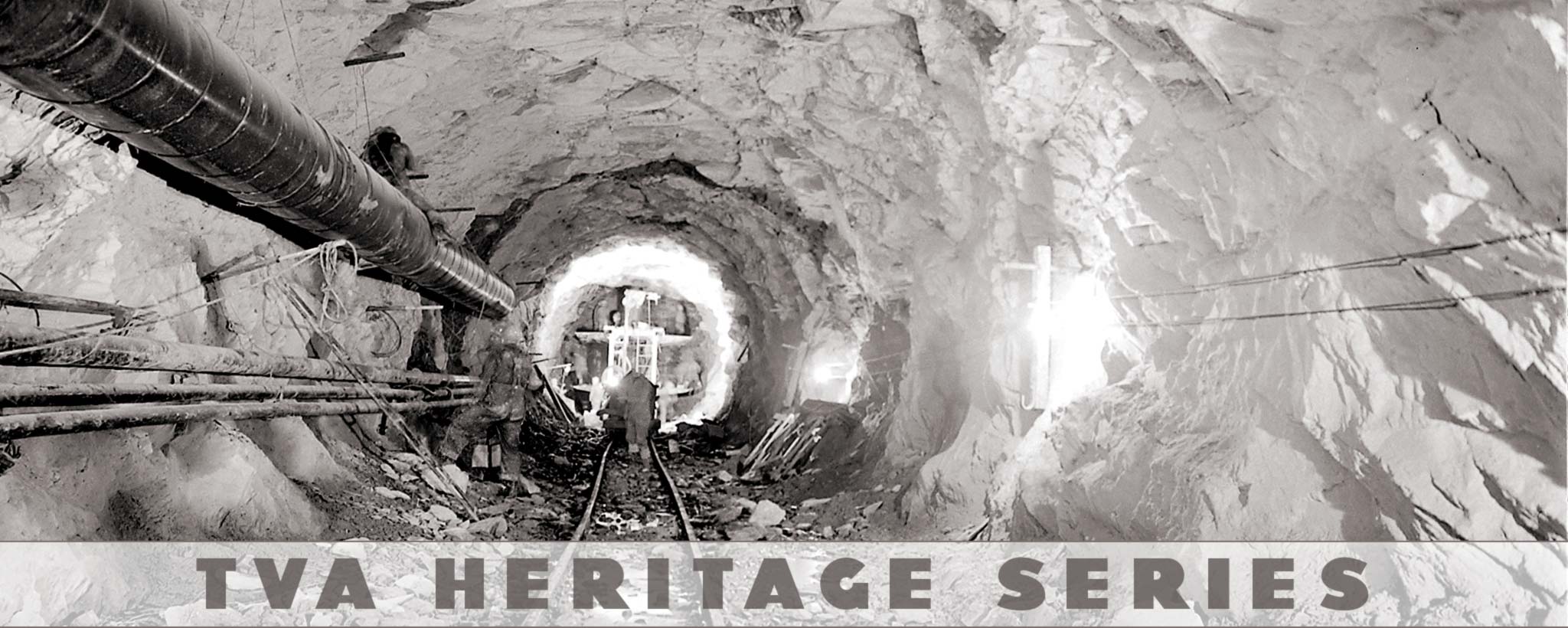

Eric Edwards is a TVA Dam Safety Engineer whose job as an inspector takes him into places that are encased in history — like an 18-foot-wide steel tube that’s shrouded by more than 8 miles of limestone.

“How did they do this?”

Edward said the question was asked many times as his team inspected every inch of the historic conduit that runs through the mountains of Cherokee County, North Carolina, and connects Apalachia Dam to a powerhouse in rural Reliance, Tennessee. But knowing

how the tunnel was blasted through 662,075 cubic yards of rock is a secret that only a 100-year-old man can tell.

Water Over the Dam

Ralph Painter was 20 when he drove a 1936 Ford convertible to the top of a mountain where men stood in the spitting snow and waited for jobs as Roosevelt’s day-of-infamy speech cracked across the camp’s radios. The morning before, Pearl Harbor had been bombed, which made the completion of the 150-foot-tall Appalachia Dam an essential cornerstone of the national war emergency program.

The dam’s purpose: was to provide hydropower for the aluminum war industry and later as a source of cheap power for residents of East Tennessee and western North Carolina.

“There was a little-ole shack up there that had two potbelly stoves in it,” Painter said. “Bout five o’clock, a man closed up his books and asked how many were left. They told him just one.

“‘What kinda job you want?’ that man asked me. See, everybody was wanting to either drive a truck or run equipment, you know. Well, I followed him out the door and told him I just wanted a job. Any job. He said, “You wanna work tonight?’”

Painter stayed on the mountain and began his shift around midnight. His first job on the project was to pick up rocks for $.50 an hour.

“That was a lot of money back then,” Painter said. “We had to pick all them rocks up to get down to bedrock before we could pour the dam.”

Once the rock job was complete the following February, Painter ran a small vibrating machine that packed concrete and forced the cement’s milky sludge to rise through the pea gravel and slick the dam’s forms. He even advanced to a medium-size vibrator, but at 130 pounds, Painter wasn’t big enough to run the larger machines.

Superstitions of Safety

And the 8-mile tunnel? Painter said the men who bored the 42,706-foot-long hole were New Yorkers who had dug the subway tunnels under New York City.

A 1942 Asheville Citizen-Times report confirms:

“Boomers are right, tough babies, and maybe it’s just as well, for you can’t blast a way through solid rock with kid gloves on. Just now, a couple of hundred of their rough and ready but rigidly select fraternity have come from jobs in California, New York state, Honolulu, Trinidad, and points west, north, east, and south, and assembled in the North Carolina mountains to build an eight-mile-long tunnel for the Apalachia dam….”

“Most of them have worked together before, for there are not any too many experienced tunnel drillers, and when a job is to be done, it’s the regular gang that shows up. For instance, [two of the foremen] worked together on the Sixth avenue subway in New York City. Now they are working together again by virtue of a bit of a fluke, the fluke being [one of the foremen] could not be located for the sailing of two boatloads of drillers bound for Ireland.”

The article went on to detail a “no-whistling” superstition that each driller believed kept them safe inside the tunnel.

By the Numbers

Despite precautions, seven men died, and 173 were injured during the 11 months it took to install Apalachia’s penstock. The record-breaking feat tallied 2.5 million work hours. Dam construction claimed one life and injured 95 during the 7.5 million total work hours it took to pour the 448,349 cubic yards of concrete that continue to tame the Hiwassee River.

For reference, that’s enough concrete to pour a standard residential driveway from Nashville to New Orleans.

“TVA would never build anything like this now for a variety of reasons,” Edwards said. “But when you’re walking through there and are thinking about how it was built at such a moment in time to literally win a war, it puts it into a whole new perspective.

“This was a life-altering time for the guys who built it, and when something makes such an impact that a 100-year-old man can still recall specifics about it 80 years later, that really speaks to the magnitude of what they did back then. And for me, hearing a first-person account like this makes me appreciate it all even more.”

Although the Apalachia’s penstock may be old, Edwards’ two-day inspection of the historic conduit found it to be sound.

“We’ve got some minor repairs that may be needed in the future, but right now, everything is in good shape.”