Articles

Whom the Guns Salute

One of TVA's most-decorated veterans, Gunnery Sergeant Charles Sweeney, died after a fatal car crash in October. We remember both his service and some of his best stories.

Gunnery Sergeant Charles Sweeney was a pig farmer, philanthropist, retired TVA laborer at Cumberland Fossil Plant, Marine sniper and a special operations officer. During his 30-year military career, he guarded two American presidents, the secretary of state and multiple generals. He served in wars from Vietnam to Desert Storm, spent 19 years overseas, was awarded two Purple Hearts, two Navy Commendation Medals and a total of 64 medals and ribbons.

He spoke five foreign languages, had two master’s degrees and acquired more than 75 military diplomas. But of all the training, linguistics courses and special ops certifications, Sweeney once told a friend that etiquette school was his favorite.

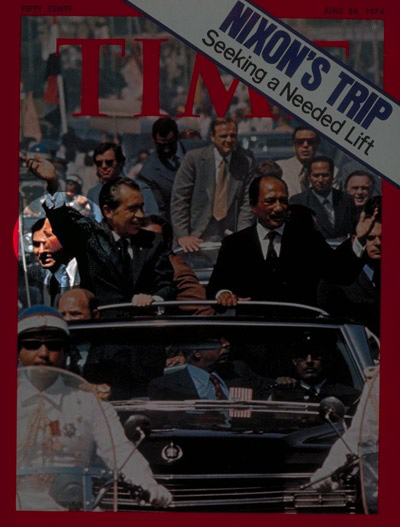

Sweeney, as part of President Nixon's security detail, on the cover of Time Magazine.

Po’ Boys at the White House

“Etiquette?” The friend asked.

“Yeah,” Sweeney said. “I had to learn what fork to eat with and how to ballroom dance.”

The friend chuckled. “Well, did you ever use that training?”

“I danced with the First Lady. Twice.”

“You mean Barbara Bush?”

“Yes,” Sweeney said.

“I’ve always heard good things about her.”

“When I was working at the White House, sometimes she’d come out there and say, ‘Sergeant, come with me.’”

Sweeney told of a wall lined with refrigerators, each stuffed with lunch meat. Then, in an awe-shucks kind of way, the Marine talked about how he and the First Lady would often have dinner together at the White House.

“She’s the nicest lady you’ll ever meet,” Sweeney said. “And she sure makes a good sandwich.”

Up in Smoke

The Marines flew Sweeney into Da Nang, Vietnam in 1971. Sweeney recalls landing a few hours before daylight, and after chow, the greenhorn Marine got his first order on foreign soil.

“You! Burn the [privies]!” said a gunny sergeant.

Sweeney did as he was told. He dowsed his assigned outhouse will five gallons of diesel and lit it on fire. Smoke rolled. The sky turned black. A 100-foot fireball blazed above the company.

“SWEENEY!”

While standing beside the raging inferno, the young private first class received his official welcome to Vietnam. After a salty critique from his superior, Sweeney learned that “burn the privies” simply meant remove the sawed-off slop drum from beneath the makeshift toilet, add the diesel fuel to the green waste and then burn only the container’s contents — not the entire company’s outhouse.

“You know, it usually took a Marine about two weeks to get to the front lines once he entered the country,” Sweeney recalled. “Somehow I made it in less than three days.”

Scars of the Past

Sweeney was quick to talk about the funnies, but hardly spoke of combat. At times he would mention things — short snippets that gave his closest friends and coworkers a peek into the past and the root cause of the soldier’s PTSD — but few details beyond, “we took care of it.”

Yes, Sweeney always took care of children. When given an assignment to collect presents for Toys for Tots, it took a convoy of semi-trucks to haul the 40,000 gifts that were donated once he got help from a retired Marine. The world knows Sweeney’s friend as Fred Smith, CEO of FedEx.

And when Sweeney was stationed in the Philippines, he saw a group of orphans on the streets who should have been in school. After inquiring as to why, the soldier enrolled the children and paid their tuition from his own wages.

Years later, he brought his hogs to the Tennessee Farm Bureau’s Ag in the Classroom Day, so all the fourth graders in Houston County could pet a real pig at a local farm while they learned the importance of agriculture. And while he was working as a farmer, a TVA laborer and working a third job in town, Sweeney also found time to substitute teach at Houston County Middle School.

Kids talk.

They said the retired Marine would always give out the teacher’s assignments, then lean back in his chair and prop his feet up on the desk while he gave himself a manicure with a Bowie knife.

The children did their homework.

The Roots of His Raising

Sweeney’s accolades and distinguished service could have easily earned him a spot in Arlington National Cemetery, but his burial didn’t take place on the banks of the Potomac. The soldier’s job had always been to stay out of the spotlight but be ready to take a bullet for our nation’s leaders.

Sweeney avoided fanfare, even after his retirement because he only wanted to be remembered as the everyday pig farmer who loved Erin, Tennessee, and served his country as an exemplary Marine.

On Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021, a guard of rifles echoed throughout Pollard Branch as Gunny Sergeant Charlie Sweeney was laid to rest on a hillside in Houston County. Sweeney’s grave overlooks a hog pen and the family farm the humble soldier called home.